|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

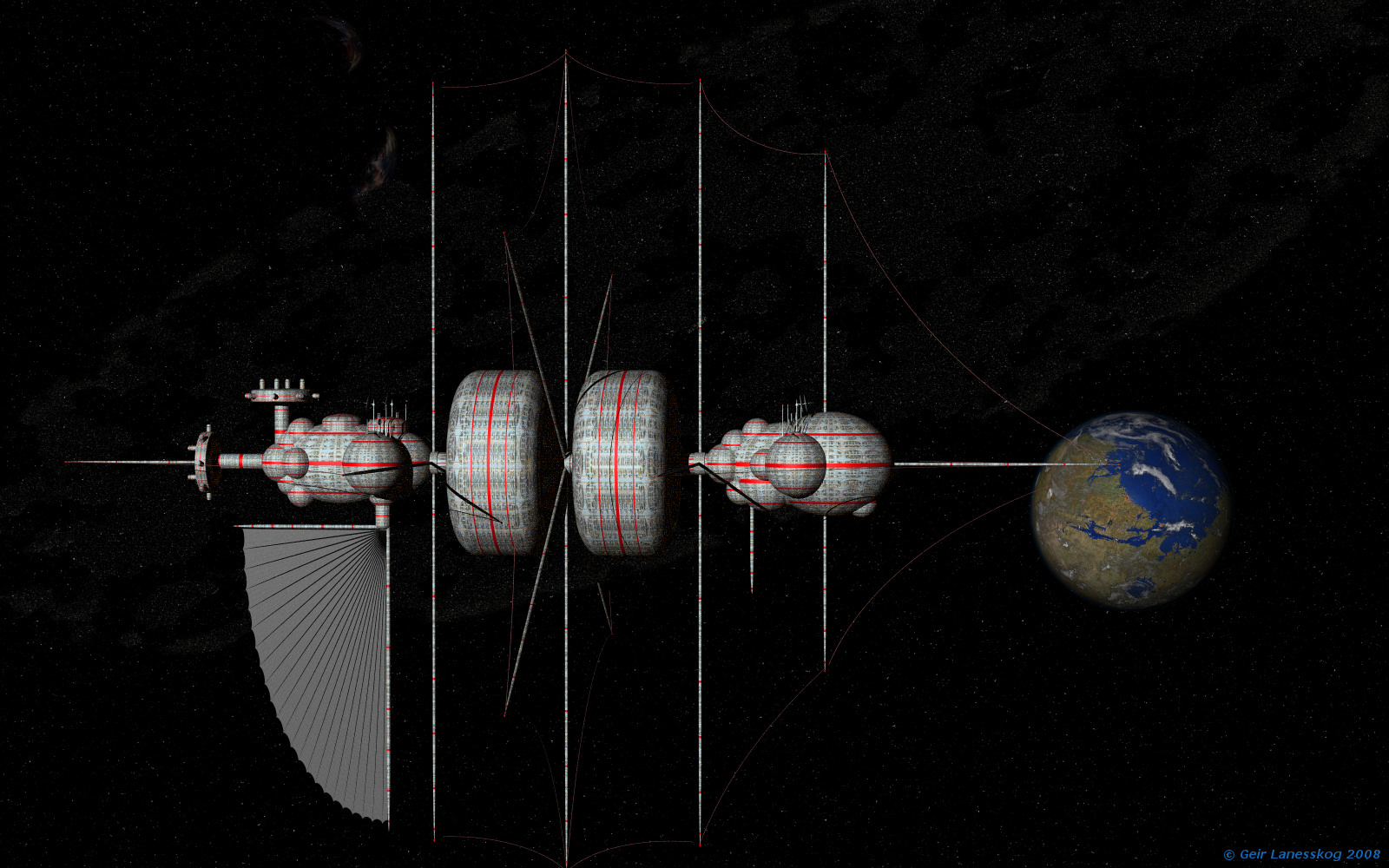

Bifrost Crossing

I spent six months on Bifrost, slowly crossing the gulf between Earth and Mars. Bifrost was the second oldest cycler, after the Aldrin, and by far the oldest and largest still in operation. It'd been independent since the Colonial War, sending a delegate to the Near Earths Congress, but otherwise minding its own business. After the Secession War, the cycler habitat retained strictly neutrality. It had gotten rebuilt, remodeled and repainted dozens of times over its four plus centuries of existence.

The only reason I was still alive was because of Bifrost's refugee policy. Anyone who could make it to an airlock was guaranteed passage, life support constraints allowing, to the next destination. After the Secession War, that's how a lot of Earthers got to Mars and how a lot of Martians got to Earth -- even into the twenty-sixth as refugees fled wars on Mars and mayhem on Earth. Of course, you had to buy or negotiate a way off once you got to the next stop. Otherwise, the Frosties indentured you for a full cycle and then paid your way.

It's a nice place. The Frosties make a bundle on the cargo trade, loading up shuttled goods from one planet and delivering them to shuttles from the other. The magsail masts use hardly any fuel, so the hab can cycle practically forever. There are two counter rotating habitat rings, disparagingly called the Barrels. The Frosties adjust the spins toward the destination world's gravity during the passage. They're really quite comfortable, even in refugee housing.

Most of the Frosties don't spend much time in the spin sections. The Barrels are for passengers and children. The domes of the forward habitat are the homes and workplaces of most of Bifrost's four thousand people. They were a strange lot, especially to a kid from the rich neighborhoods of Mombasa, but I got to like them. They had a great sense of humor, hardly any obnoxious taboos, and a surprising amount of tolerance for such an isolationist bunch. Guess they just didn't want anyone trying to tell them what to do. They offered me a job, flying their onboard shuttles. It was tempting, but I had to turn it down. I couldn't risk going near Earth again. Mars would be my future.

--Excerpt from notes of Walker Tsume's unpublished memoirs, early twenty-sixth century.

All pages and images ©1999 - 2009

by Geir Lanesskog, All Rights Reserved

Usage Policy

![]()